Table of Contents

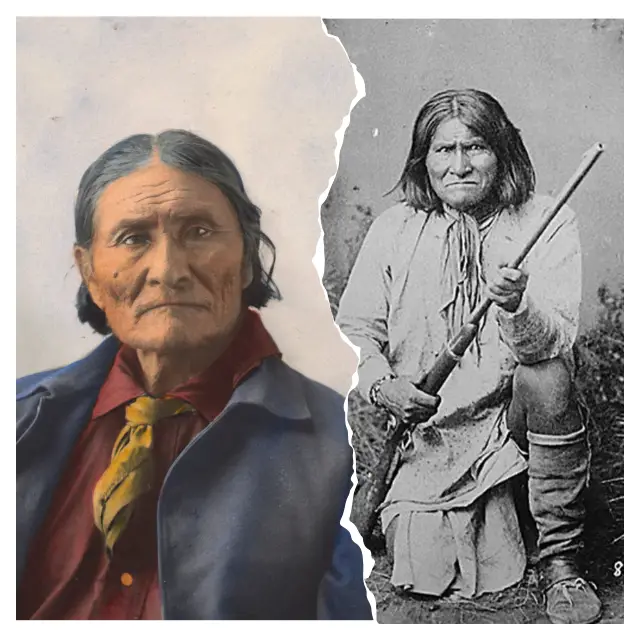

Geronimo (1829-1909) was a courageous Apache leader and medicine man who stood up to anyone, Mexican or American, who tried to evict his people from their tribal territory.

He eluded capture and life on a reservation on several occasions, and on his final escape, a quarter of the United States’ standing army chased him and his companions. Geronimo was the last Native American leader to formally surrender to the US soldiers when he was caught on September 4, 1886. He was a prisoner of war for the last 23 years of his life.

Geronimo’s life story frequently deviates from legend: he was portrayed as a terrifyingly fierce warrior in American and Mexican culture, as well as a symbol of valor for World War II paratroopers who chanted his name as they leaped off planes. One of his biographers dubbed him “the most famous North American Indian of all time.”

Geronimo, on the other hand, was less of a mythic character to his people in reality. According to The Washington Post, he was relatively unknown beyond the Chiricahua Apache until he was in his middle years.

“Geronimo was not a very important guy in our community,” says Michael Darrow, a tribal historian with the Fort Sill Apache tribe. “He wasn’t a commander.” Geronimo would not have been a big thing to the tribe a century ago.

Geronimo, on the other hand, typified the stereotype of the fearsome warrior Indian to many Americans in the nineteenth century. He embodied the language that may be used to justify transferring Indians into reservations in the name of “protecting” Europeans. That rhetoric was also used to the Apache as a whole.

“One of the terms that is frequently used in writing about Apache is warriors,” Darrow explains. The Apache language, on the other hand, does not have a word that means “warrior.” “As a result of history texts and popular portrayals of Apache in novels and movies, Apache are portrayed as savage and warlike.”

Geronimo’s own account of his youth tells a different tale.

Geronimo’s Early Life.

There are two versions of Geronimo’s birth date and location. It happened in 1823 in the upper Gila River Valley in what is now New Mexico, according to Robert M. Utley, historian and author of “Geronimo.” But, as an octogenarian, Geronimo narrated his life tale in “Geronimo’s Story of His Life: As Told to S.M. Barrett,” he said he was born in 1829 in what is now Arizona. In any case, the land would have been part of Mexico until the Mexican Cession in 1848, which followed the Mexican-American War, and the Gadsden Purchase in 1854.

What is undeniable is that Geronimo was born into the Chiricahua Apache tribe’s Bedonkohe band and given the name Goyahkla, which means “one who yawns.” He was the fourth of eight children, four boys and four girls, in his family. Geronimo describes his homeland at the Gila River’s headwaters in “Geronimo’s Story of His Life: As Told to S.M. Barrett“:

The scattered valleys contained our fields; the boundless prairies, stretching away on all sides, were our pastures; the rocky caverns were our burying places. This range was our fatherland; among these mountains were hidden our wigwams; the scattered valleys contained our fields; the boundless prairies, stretching away on all sides, were our pastures; the rocky caverns were our burying places.

Geronimo describes his boyhood, which included planting crops, picking wild tobacco, grinding grain, and going on treks to gather nuts and berries. He began “the pursuit” when he was about 8 or 10 years old, hunting buffalo, deer, antelope, and elk, and slaying only those that the tribe need. He claimed to have killed a lot of bears with a spear and a lot of mountain lions with arrows.

Importantly, Geronimo claims that he never saw a missionary or a priest as a child. “We’d never seen a white person before.”

What Does the Name ‘Geronimo!’ Mean?

The origin of the name “Geronimo” is a point of contention. While directing Apache attacks, the youthful Goyahkla gained the moniker. Some historians say it stems from frightened Mexican soldiers shouting the name of St. Jerome, the Catholic saint, while they battled Geronimo. Others claim it’s just a misspelling of “Goyahkla.”

Whatever the origins of the name “Geronimo,” it gained fresh life long after the leader’s death: paratroopers cried “Geronimo!” before jumping out of planes during World War II, an homage to his valor.

Geronimo Resists Reservations

The Apache faced new challenges—and foes—as the United States expanded westward. The Mexican-American War ended in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Much of what is now the American Southwest was transferred to the United States by Mexico, including land that the Apaches had occupied for centuries. In 1854, the Gadsden Purchase granted the United States even more land in what is now Arizona and southwestern New Mexico.

The Chiricahua Apaches were given a reservation in 1872 that covered at least a piece of their territory, but they were quickly expelled and forced to join other Apache clans on the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. In the next decade, a rebellious Geronimo and his supporters broke out of the San Carlos Reservation three times. His familiarity with the neighboring hills aided him in eluding his pursuers.

The more Geronimo escaped and the longer he remained at large, the more embarrassed the US military and officials became. As he dodged skirmishes with law enforcement, Anglo-Americans, and Mexicans, he seemed to believe that no bullets could hurt him. Despite being injured several times, he always recovered. He became a sensation in the press.

Tragedy and Retaliation

In 1858, the Bedonkohe Apache traveled south to Old Mexico, staying just outside the town of Kaskiyeh and trading there every day. The camp’s women and children stayed. When the tribesmen returned one afternoon, they discovered that Mexican troops had stormed the camp, killing all of the guards, seizing the horses and weapons, and slaughtering many of the women and children. Geronimo’s mother, wife Alope, and their three children were among the victims. According to his biography:

That night, I did not vote for or against any measure; but, it was decided that with just eighty warriors remaining, no weaponry or supplies, and being encircled by Mexicans far inside their own country, we could not hope to fight successfully. As a result, our commander, Mangus-Colorado, gave the order to depart immediately in complete secrecy for our homes in Arizona, leaving the dead on the field. I stayed there until everything was finished, unsure of what I would do – I didn’t have a weapon, didn’t want to fight, and didn’t think of recovering the bodies of my loved ones because that was illegal. I didn’t pray, and I didn’t make any plans, since I didn’t know what else to do. I ultimately followed the group in silence, maintaining just within hearing distance of the Apaches’ receding footsteps.

The group returned to its own village a few days later. A council was called by Chief Mangus-Colorado (or Mangas Coloradas). The Bedonkohe were adamant about going to war with Mexico. The Chokonen Apache, commanded by Cochise, and the Nedni Apache, led by Whoa, were despatched to petition adjacent tribes for assistance, which Geronimo received.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Geronimo spent the next quarter-century “attacking and eluding both Mexican and American troops, pledging to kill as many white men as he could.”

But, as Utley argues in an email, thinking of Geronimo as a nationalist chief battling for the preservation of his homeland is a mistake. “On every level, you’re wrong. He wasn’t a patriot, a chief, or a soldier fighting for his country.” He was fighting for a cause that he believed in.

Not Surrender, but Treaty Negotiation

Prior to the United States government’s decision in the 1870s to relocate all Native Americans in the Southwest to reservations, Geronimo claimed that the greatest wrong done to his tribe occurred in 1863, when chief Mangus-Colorado agreed to a peace treaty with US General Joseph Rodman West at Apache Tejo, New Mexico (Fort McLane) in exchange for provisions for his people. Mangus-Colorado deported approximately half of the tribe to New Mexico, where they were detained instead of making peace. For attempting to flee, West ordered the chief’s execution, and he was tortured and slain that night.

Out of dread, Geronimo and his followers retreated to the mountains. Until he was taken as a prisoner of war on the San Carlos Reservation, US troops continued to strike their encampment. However, in 1885, Geronimo and a group of 135 men, women, and children escaped capture and remained free for nearly a year.

For months, they were hunted by 5,000 US soldiers and 3,000 Mexicans led by US General George R. Crook. They did, however, manage to flee once more. General Nelson Miles resumed the pursuit, eventually forcing Geronimo to surrender near Fort Bowie on September 4, 1886. The Apache were simply fatigued and outmanned at that point. The American-Indian Wars were thought to have ended with his “surrender.”

Geronimo, on the other hand, believed he had met with Miles to negotiate a treaty, not to surrender. Miles gained extra credibility by claiming to be the military commander who persuaded Geronimo to surrender. Darrow claims, “It was obviously not an unconditional surrender as it had been depicted.”

On Sept. 8, 1886, Geronimo and 400 Apache were transferred to Fort Pickens, Florida, following the capitulation. They were relocated to Alabama after a few years, and then to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in 1894.

“Geronimo doesn’t seem to have done much to try to assist the tribe as a whole before his imprisonment,” Darrow explains. After the tribe was imprisoned, he tried to use every power he had to get them released. The Apache were told that they would not be imprisoned for more than two years and that they would be given their own reserve and country. Darrow’s grandmother, on the other hand, was a prisoner of war in Alabama when she was born in 1892.

The Death and Legacy of Geronimo

From 1894 until his death on February 17, 1909, Geronimo lived at Fort Sill. Geronimo left the Oklahoma reservation during his years there to perform in Pawnee Bill’s Wild West show, billed as “The Worst Indian That Ever Lived.” Even though his petitions for the restitution of Chiricahua land were denied, he attended the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair and President Theodore Roosevelt’s inauguration, where he was put on display.

Geronimo fell off his horse on the way back to Fort Sill from Lawton, Oklahoma, in February 1909. He was discovered the next morning with a cold that progressed to pneumonia. He was dead within a week. Geronimo was buried at Fort Sill while still a prisoner of war.

According to Darrow, his narrative served as a form of justification for keeping the tribe as POWs for nearly 30 years.

“No one was willing to put their reputation on the line to let Geronimo go,” he claims. It was in the US government’s political interests to keep them imprisoned and portray them as a violent, aggressive people who could be dangerous.

You can buy book here : From Cochise to Geronimo: The Chiricahua Apaches .

Source :