Table of Contents

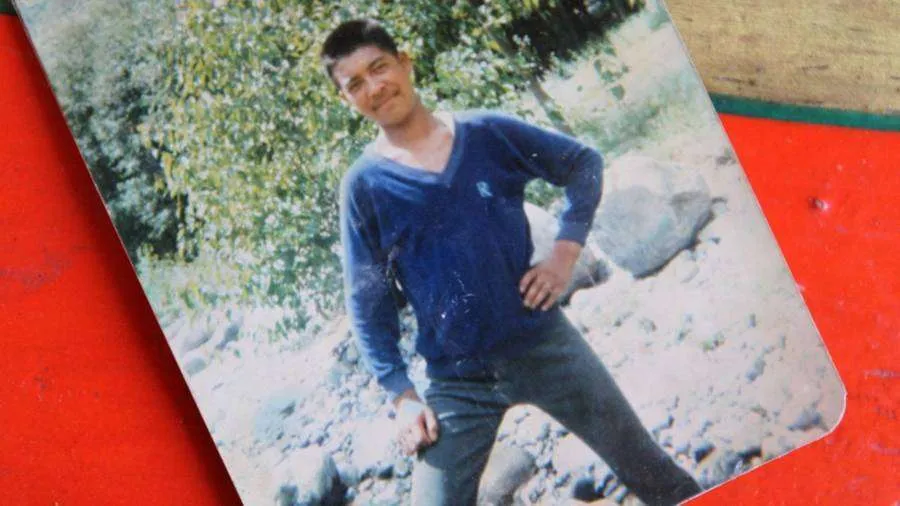

Hundreds of people have passed by Tsewang Paljor, also known as Green Boots, but few of them are aware of his story.

The human body was not built to withstand the extremes found on Mount Everest. Aside from the risk of death from hypothermia or a lack of oxygen, the sudden elevation change can cause heart attacks, strokes, and brain swellings.

In the mountain’s Death Zone (the area above 26,000 feet), the level of oxygen is so low that climbers’ bodies and minds begin shutting down.

With only a third of the amount of oxygen there is at sea level, the climbers face as much danger from delirium as they do from hypothermia. When Australian climber Lincoln Hall was miraculously rescued from the Death Zone in 2006, his saviors found him stripping off his clothes in the sub-zero temperatures and babbling incoherently, believing himself to be on a boat.

Hall was one of the lucky few to make the descent after being beaten by the mountain. From 1924 (when adventurers made the first documented attempt to reach the peak) to 2015, 283 people have met their deaths on Everest. The majority of them have never left the mountain..

One of the first people to attempt to climb Everest, George Mallory, was also one of the mountain’s first victims.

Climbers are also susceptible to “summit fever,” a type of mental illness. Summit fever is when a climber is so focused on getting to the top of a mountain that they ignore their body’s warning signs.

Other climbers may become dependent on a good Samaritan if something goes wrong during their ascent, and this summit fever could be fatal. David Sharp’s death in 2006 sparked outrage because approximately 40 climbers allegedly passed him by on their way to the summit, oblivious to his near-fatal condition or abandoning their own attempts to stop and help.

Getting live climbers out of the Death Zone is dangerous enough, but getting their bodies out is nearly impossible. Many unfortunate mountaineers are forever frozen in time, serving as macabre landmarks for the living.

The body of “Green Boots,” one of the eight people killed on the mountain during a blizzard in 1996, must be passed by every climber en route to the summit.

The body is curled up in a limestone cave on Mount Everest’s northeast ridge route, earning its name from the neon green hiking boots it wears. Despite their proximity to the summit, everyone passing through is forced to step over their legs, a powerful reminder that the path is still treacherous.

Green Boots is thought to be Tsewang Paljor (whether it is Paljor or one of his teammates is still a point of contention), a member of an Indian four-man climbing team who attempted to reach the summit in May 1996.

The 28-year-old Paljor was an officer with the Indo-Tibetan border police who grew up in Sakti, a village near the Himalayan foothills. He was ecstatic to be chosen for the elite team that aimed to be the first Indians to reach the summit of Everest from the north side.

In a flurry of excitement, the team set off, not realizing that most of them would never leave the mountain. Tsewang Paljor and his teammates were completely unprepared for the dangers they would face on the mountain, despite their physical strength and enthusiasm.

The expedition’s sole survivor, Harbhajan Singh, recalled being forced to retreat due to steadily worsening weather. Despite his efforts to persuade the others to return to the relative safety of the camp, they continued on without him, overcome by summit fever.

Tsewang Paljor and his two teammates did indeed reach the summit, but they were caught in a deadly blizzard on their way down. The Green Boots were found huddled and frozen in an eternal attempt to shield themselves from the storm by the first climbers seeking shelter in the limestone cave.

See What Happened When Hikers Discovered George Mallory’s Body On Mount Everest

Watch the moment George Mallory’s body was discovered on Mount Everest by hikers.

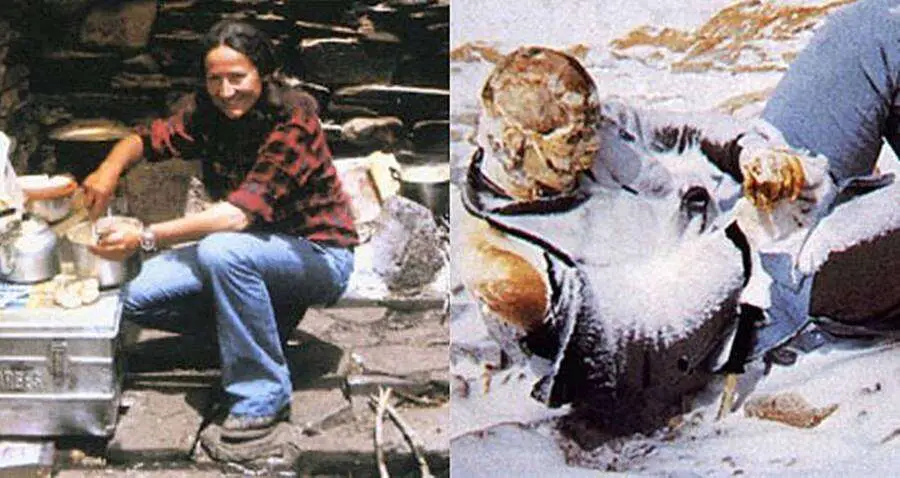

George Mallory was a well-known British explorer and mountaineer. Mallory was a member of a British expedition to the summit of Mount Everest long before Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became the first to do so.

The 1924 expedition was the third in a series that began in 1922 and ended in 1924. Mallory, who was 37 at the time, jumped at the chance to participate in such an exciting adventure, fearing that as he grew older, it would become impossible.

The team set out at the end of May and had no trouble reaching the campsites above 20,000 feet.

Mallory and his climbing partner, Andrew Irvine, left Advanced Base Camp on June 4, 1924, and set out on their own. According to the porters left behind at the camp, Mallory was confident that the pair would be able to summit the mountain and return to the camp before nightfall.

He was completely wrong. The two climbers vanished that day, and it took more than 70 years for their bodies to be discovered.

Climbers from the BBC’s “Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition” arrived at Everest in 1999 with the sole goal of finding the pair. Despite the fact that Mallory and Irvine had been missing for 75 years, the odds were in their favor. Everest’s constant freezing temperatures and permafrost layer almost perfectly preserve the bodies of climbers who perish on its slopes.

Conrad Anker noticed a large, flat white rock on the mountain’s northern slopes on May 1. On closer inspection, he realized he was looking at George Mallory’s bare back, not a rock. The majority of his clothing had degraded over time, but the parts of his body that had been covered were still in good condition.

Irvine’s body was never discovered, but his climbing axe was discovered about 800 feet above Mallory’s. The location of the axe and a rope found tied around Mallory’s waist led researchers to believe that Mallory had been tied to Irvine and either fell, dragging Irvine with him, or cut himself free before falling. A fall was blamed for the couple’s deaths.

Whether George Mallory and Andrew Irvine ever reached the summit is unknown, though experts believe Mallory was climbing down the mountain rather than up it, based on the position of his body. According to survivors of the 1924 climbing expedition, Mallory was carrying a camera to document his and Irvine’s success if they reached the summit, but no camera has ever been found.

Although several expeditions in recent years to locate the film have proven fruitless, Kodak experts have stated that if a camera is ever found, the film could likely still be developed.

The Life And Death Of Hannelore Schmatz, The First Woman To Perish On Mount Everest

Hannelore Schmatz accomplished the unimaginable in 1979 when she became the fourth woman in the world to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Unfortunately, her glorious ascent to the summit of the mountain would be her final.

Hannelore Schmatz, a German mountaineer, enjoyed climbing. Schmatz and her husband, Gerhard, set out on their most ambitious expedition yet in 1979: to summit Mount Everest.

While the husband and wife triumphed at the summit, their descent ended in tragedy when Schmatz died, making her the first woman and German national to die on Mount Everest.

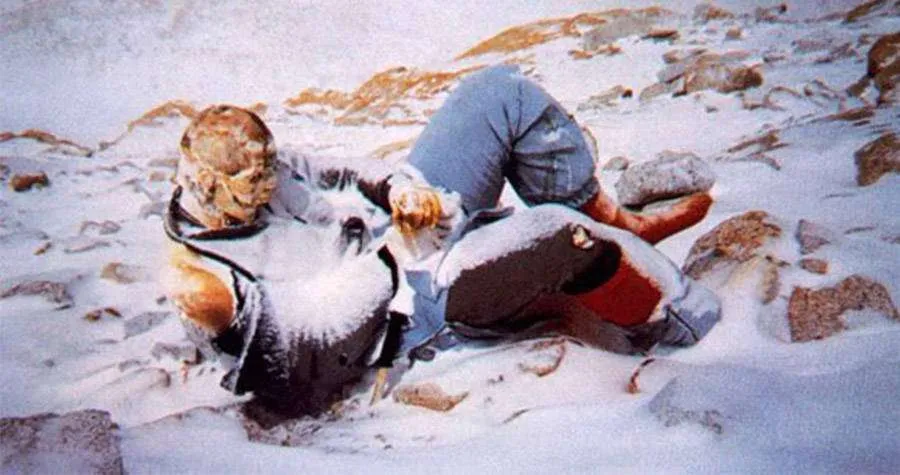

Hannelore Schmatz’s mummified body, which could be found by the backpack that was pressed against it, would serve as a gruesome warning for years to other mountain climbers who tried to do the same thing that killed her.

An Experienced Climber

Only the world’s most experienced climbers take on the life-threatening conditions that accompany the ascent to Everest’s summit. Hannelore Schmatz and her husband, Gerhard Schmatz, were seasoned mountaineers who had trekked to some of the world’s most difficult summits.

Hannelore and her husband returned to Kathmandu in May 1973 after a successful expedition to the top of Manaslu, the world’s eighth highest peak at 26,781 feet above sea level. They didn’t waste any time deciding on their next challenging climb.

For unknown reasons, the husband and wife decided it was time to conquer Mount Everest, the world’s highest peak. They asked the Nepalese government for permission to climb the most dangerous peak on Earth, and then they started getting ready.

Since then, the two have climbed a mountain peak every year to improve their ability to adjust to high altitudes. The mountains they climbed grew higher as the years passed. After another successful climb to Lhotse, the world’s fourth highest mountain peak, in June 1977, they finally heard that their request to climb Mount Everest had been approved.

Hannelore was in charge of the technical and logistical planning for their Everest hike. Her husband said that she was “a genius” when it came to finding and transporting expedition supplies.

Because it was still difficult to find adequate climbing gear in Kathmandu in the 1970s, they had to ship their equipment from Europe to Kathmandu for their three-month expedition to Everest’s summit.

Hannelore Schmatz reserved a warehouse in Nepal for the storage of their equipment, which weighed several tons. They needed to put together their expedition team in addition to the equipment. In addition to Hannelore and Gerhard Schmatz, six other experienced high-altitude climbers joined them on Everest.

New Zealander Nick Banks, Swiss Hans von Känel, American Ray Genet — a seasoned mountaineer with whom the Schmatzs had previously collaborated — and fellow German climbers Tilman Fischbach, Günter Fuchs, and Hermann Warth were among them. Hannelore was the group’s only female member.

Everything was ready to go when the group of eight set out on their trek in July 1979, with five sherpas — local Himalayan mountain guides — to lead the way.

Summiting Mount Everest

The group hiked at an altitude of about 24,606 feet above sea level during the climb, a level of altitude known as “the yellow band.”

They then followed the Geneva Spur to the South Col, which is a sharp-edged mountain point ridge at the lowest point between Lhotse and Everest, at a height of 26,200 feet above ground. On September 24, 1979, the group decided to set up their final high camp at the South Col.

However, a multi-day blizzard forces the entire camp to retreat to Camp III’s base camp. Finally, they attempt to return to the South Col point, splitting into large groups of two this time. Hannelore Schmatz is in one group with other climbers and two sherpas, while the rest of her family is in the other with her husband.

Gerhard’s group is the first to return to the South Col, arriving after a three-day climb and setting up camp for the night.

The group, which had been traveling the harsh mountain landscape in groups of three, was about to begin the final phase of their ascent toward the summit of Everest when they arrived at the South Col point.

Gerhard’s group continued their hike toward Everest’s peak early on Oct. 1, 1979, while Hannelore Schmatz’s group was still making their way back to the South Col.

Gerhard Schmatz, who is 50 years old, became the oldest person to summit the world’s highest mountain peak when his group reached the south summit of Mount Everest at around 2 p.m. While the group rejoices, Gerhard describes the team’s difficulties on his website, noting the hazardous conditions from the southern summit to the peak:

“Due to the steepness and the bad snow conditions, the kicks break out again and again. The snow is too soft to reach reasonably reliable levels and too deep to find ice for the crampons. How fatal that is, can then be measured, if you know that this place is probably one of the most dizzying in the world.”

Gerhard’s group quickly makes their way back down, encountering the same difficulties they had during their climb.

When they arrived safely back at the South Col camp at 7 p.m. that night, his wife’s group had already set up camp to prepare for Hannelore’s group’s own ascent to the summit, having arrived around the same time Gerhard had reached the summit.

Gerhard and his companions try to persuade Hannelore and the others not to go because of the bad snow and ice conditions. Hannelore, on the other hand, was “indignant,” as her husband put it, and wanted to conquer the great mountain as well.

Hannelore Schmatz’s Tragic Death

At around 5 a.m., Hannelore Schmatz and her group set out from the South Col to reach Mount Everest’s summit. As the weather began to deteriorate, Hannelore and her husband, Gerhard, made their way back down to the base of Camp III.

Gerhard learns that his wife has reached the summit with the rest of the group via the expedition’s walkie-talkie communications around 6 p.m. Hannelore Schmatz was the world’s fourth female mountaineer to summit Everest.

Hannelore’s descent, on the other hand, was fraught with peril. According to the surviving group members, Hannelore and American climber Ray Genet, both strong climbers, became too exhausted to continue. Before continuing their descent, they wanted to set up a bivouac camp (a sheltered outcropping).

Sherpas Sungdare and Ang Jangbu, who were with Hannelore and Genet at the time, cautioned them against taking the risk. They were in the so-called Death Zone, an area where conditions are so dangerous that climbers are most likely to perish. The climbers were advised to press on so that they could return to the base camp further down the mountain.

But Genet had reached his breaking point and remained, eventually succumbing to hypothermia.

Hannelore and the two other sherpas, shaken by the loss of their comrade, decide to continue their descent. But it was too late; Hannelore’s body had already begun to succumb to the harsh weather. Her last words, according to the sherpa who was with her, were “Water, water,” as she sat down to rest. She passed away there, in her backpack.

One of the sherpas stayed with Hannelore Schmatz’s body after she died, resulting in the frostbite of a finger and some toes.

Hannelore Schmatz was the first woman and German to die on the slopes of Everest.

General Douglas MacArthur – US History Definition

General Douglas MacArthur spent his entire life in the United States Army, from birth to death. He was a five-star US army commander who was clever, contentious, egotistical, courageous, imperiled, and very bright. Read More >>

Schmatz’s Body Is Used As A Scary Marker For Others

“Nonetheless, the team came home,” her husband Gerhard wrote after her tragic death on Mount Everest at the age of 39. But I’m all alone without Hannelore.”

Hannelore’s body remained horribly mummified by the extreme cold and snow where she took her last breath, right on the path many other Everest climbers would take.

Her death became famous among climbers due to the state of her body, which was frozen in place for all to see along the mountain’s southern route.

Her eyes remained open and her hair fluttered in the wind as she continued to wear her climbing gear and clothing. Other climbers began calling her the “German Woman” because of her seemingly serene posture.

Arne Naess, Jr., a Norwegian mountaineer and expedition leader who successfully summited Everest in 1985, described his encounter with her body as follows:

I can’t escape the sinister guard. Approximately 100 meters above Camp IV she sits leaning against her pack, as if taking a short break. A woman with her eyes wide open and her hair waving in each gust of wind. It’s the corpse of Hannelore Schmatz, the wife of the leader of a 1979 German expedition. She summited, but died descending. Yet it feels as if she follows me with her eyes as I pass by. Her presence reminds me that we are here on the conditions of the mountain.

In 1984, a sherpa and a Nepalese police inspector attempted to recover her body, but both men died. Hannelore Schmatz was eventually taken by the mountain after that attempt. A gust of wind pushed her body over the side of the Kangshung Face, where it would never be seen again, lost to the elements forever.

Her Legacy In Everest’s Death Zone

Schmatz’s body was part of the Death Zone, where ultra-low oxygen levels rob climbers of their ability to breathe at 24,000 feet, until it vanished. Mount Everest has about 150 bodies, many of which are in the Death Zone.

Despite the snow and ice, Everest’s relative humidity remains relatively low. The bodies are remarkably well preserved, and they serve as cautionary tales for anyone who attempts something foolish. Apart from Hannelore’s, the most famous of these bodies is George Mallory’s, who attempted but failed to reach the summit in 1924. Climbers discovered his body 75 years later, in 1999.

Over the years, an estimated 280 people have died on Everest. Until 2007, one out of every ten people who attempted to climb the world’s highest mountain died. Because of more frequent trips to the top, the death rate has actually increased and gotten worse since 2007.

Fatigue is a common cause of death on Mount Everest. Climbers are simply too exhausted, either from exertion, a lack of oxygen, or from expending too much energy, to return down the mountain once they have reached the summit. Lack of coordination, confusion, and incoherence are all symptoms of exhaustion. The brain may bleed internally, exacerbating the situation.

Hannelore Schmatz died from exhaustion and possibly confusion. Although it made more sense to return to base camp, the experienced climber felt that taking a break was the better option. If you’re too weak to continue in the Death Zone above 24,000 feet, the mountain always wins.

Source : NY Times | All The Interesting

All the information and photo credit goes to respective authorities. DM for removal please.

Read More>>>

Annie Edson Taylor AKA Barrel Annie, First To Go Over Niagara Falls in Barrel

93 Aged Florida Woman Reached 567,000 Miles In Her 1964 Mercury Classic Car