Table of Contents

In the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, high above in her gleaming two-engine Lockheed Electra, Amelia Earhart soared. The date was July 2, 1937, and alongside navigator Fred Noonan, she was en route to their next destination—Howland Island, situated 1,700 miles southwest of Honolulu. These seasoned flyers were on the final stretch of their around-the-world journey, having already completed an astonishing 20,000 miles in six weeks. But all was not well.

As their plane cruised over a desolate part of the Pacific, a sense of danger loomed. The aircraft was laden, low on fuel, and locating the minuscule island amidst the vast ocean was proving to be an immense challenge—a mere two-and-a-half-square-mile speck of land in the immense sea.

As the hours passed and the morning sun obscured her view, Earhart’s voice grew frantic and confused as she sent out clipped radio transmissions. Then, according to official records, silence ensued. This silence marked the understated beginning of one of America’s most enduring mysteries.

Now, 80 years later, this mystery continues to captivate, perplex, and baffle everyone who has sought the whereabouts of the two missing aviators since that fateful day in 1937.

Who is Amelia Earhart?

Amelia Mary Earhart was born in Atchison, Kansas, in 1897, six years prior to the Wright Brothers’ historic flight. In her 1932 book Last Flight, she recounted seeing her first airplane in 1910 at the Iowa State Fair. However, her attention at that time was more drawn to an absurd hat made from an inverted peach basket, which she had purchased for fifteen cents.

After attending school in Pennsylvania, she worked as a nurse’s aide during World War I in Canada. During her time there, she attended an exhibition featuring flying aces recently returned from Europe. The sight of planes soaring and buzzing the crowd left an indelible mark on Earhart. “I did not understand it at the time,” she wrote, “but I believe that little red airplane said something to me as it swished by.”

In 1920, she took her inaugural flight with soon-to-be record-breaking ace Frank Hawks. A year later, she was one of the few women in flight school, and in 1923, she became the 16th female to obtain her pilot’s license from the World Air Sports Federation. A year following Lindbergh’s historic flight, Earhart became the first woman to fly across the Atlantic, albeit as a passenger—a fact that perpetually bothered her. This milestone catapulted her to international fame and fortune.

In 1930, she acquired the plane that would etch her name in history, the iconic red Lockheed 5B Vega, affectionately dubbed “Old Bessie.” Since its unveiling in 1976, it has been displayed at the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum. On May 20th, 1932, exactly five years after Lindbergh’s feat, she left an indelible mark by becoming only the second person to pilot a plane solo across the Atlantic and the first woman to achieve this milestone. In 1935, she became the first person to fly solo from Hawaii to the United States mainland.

By 1937, Earhart was not just a renowned author, lecturer, and celebrity; she was a beacon of inspiration for women worldwide. She utilized her fame to encourage other women to pursue aviation, founding the organization The Ninety-Nines, which remains active to this day. “She always wanted to determine her own course,” explains Dorothy Cochrane, aeronautics curator at the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum. “She persevered in helping to establish aviation as a mode of transportation when it was still perceived as a novelty.”

The Final Flight of Amelia Earhart

In April 1936, when Earhart announced her plan to circumnavigate the globe, it captured the world’s attention. With funding from Purdue University, she acquired the much-touted “flying laboratory,” the Lockheed L-10E Electra, and took to the skies.

On March 17, 1937, Earhart initiated her journey by flying from Oakland, California, to Honolulu, Hawaii, in under 16 hours. Three days later, during takeoff from Honolulu, Earhart “groundlooped” the plane, causing substantial damage but thankfully no injuries. Nevertheless, it foreshadowed a grim future.

Two months later, she embarked on her global odyssey once more, this time traveling eastward. Her route would traverse the continental United States, the Caribbean, South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia before reaching Lae, New Guinea. From there, she planned to stop at Howland Island before returning to Oakland. Covering approximately 28,595 miles along the equator, it was an arduous journey, longer than any previously attempted.

Earhart and Noonan successfully landed at Lae on June 30 and departed on July 2, brimming with confidence and aboard a fully loaded plane. Their flight to Howland Island spanned about 2,500 miles and was estimated to take 18 hours. But they never arrived.

You might also read:

- Was Amelia Earhart Eaten by Crabs? The Enduring Mystery

- Did the Japanese Military Capture Amelia Earhart After Her Plane Crash?

- 7 Fascinating Facts About Amelia Earhart And Her Life Story

The Death of a Legend, the Birth of Many Theories

Numerous theories have emerged to explain what transpired, ranging from plausible to far-fetched. Among them, two prevalent and widely accepted explanations stand out. The first posits that they ran out of fuel and crash-landed relatively close to Howland Island, with the airplane subsequently sinking thousands of feet to the Pacific’s depths.

Officially, the U.S. government subscribes to this theory. Several books, including Elgen and Marie Long’s Amelia Earhart: Mystery Solved, present this argument based on intuitive flight techniques and records of radio transmissions with the U.S. Coast Guard patrol boat Itasca, tasked with guiding the Electra to the island.

Nauticos, renowned for its high-resolution mapping of the ocean floor and sonar surveys aiding government agencies in locating lost submarines, has undertaken multiple deep-sea expeditions over the past two decades, primarily focusing on an area around Howland Island. As of February 2017, Nauticos’ search remains ongoing.

Cochrane suggests that this tragedy might have been avoidable. Prior to departure, Earhart insisted on leaving behind a 25-foot trailing radio antenna, deeming it cumbersome and unnecessary. This antenna could have significantly enhanced the Coast Guard’s ability to pinpoint her radio signal. Cochrane also emphasizes that neither Earhart nor Noonan possessed substantial communication training and were unfamiliar with Morse Code, which could have served as a fail-safe method of communication.

Furthermore, tiny Howland Island was an ill-suited choice for a landing spot, given its mere two-mile length and one-mile width. However, the U.S. military sought to establish a Pacific outpost as a prelude to World War II and encouraged its selection. According to Cochrane, “it was… an accident waiting to happen.”

However, experts like Ric Gillespie, executive director of The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), challenge the “crash and sink” theory. Gillespie points to a wealth of evidence unearthed by TIGHAR, suggesting that the Americans missed Howland Island and continued southeast for another 350 nautical miles. There, Gillespie believes, they managed to land the plane on the coral reef barrier surrounding the uninhabited Gardner Island (now Nikumaroro Island).

Over the subsequent nights, distress radio signals emanated from this area. Despite efforts, U.S. Navy search planes failed to locate the castaways. Gillespie contends that Earhart (and potentially Noonan) survived on the island for weeks, if not months, before succumbing. In fact, a human skeleton discovered on the island in 1940 contradicted initial assertions by British authorities, who claimed the skull belonged to a short, European male.

Disputing this assessment, Gillespie enlisted anthropologist Richard Jantz from the University of Tennessee. Jantz reexamined the measurements and concluded they aligned with those of a female of European origin. In the summer of 2017, TIGHAR collaborated with the National Geographic Society, sponsoring a team of human-remains detection dogs to pinpoint the castaway’s exact location of death.

While excavations did not yield remains, ongoing efforts involve extracting human DNA from the soil, a technique previously used to recover Neanderthal DNA. Gillespie acknowledges the slim odds but remains hopeful.

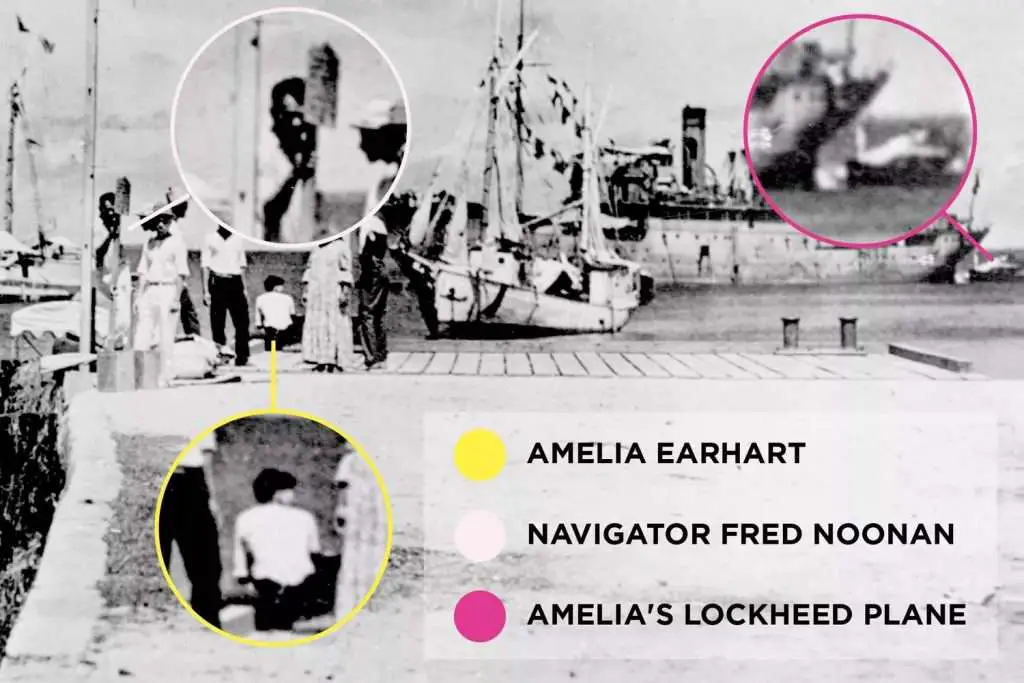

Meanwhile, more extravagant explanations persist. Recently, the History Channel aired a documentary claiming a long-lost photo as evidence that Earhart and Noonan were captured by the Japanese.

However, this photo was quickly debunked, likely predating their flight and incapable of featuring the two American flyers. Although Cochrane and Gillespie differ on what transpired 80 years ago, they both agree that the alleged photo depicting Earhart and Noonan is baseless.

Cochrane laments, “That theory had been around for years,” adding, “unfortunately, this picture that they found to be definitive is not.” Gillespie’s critique is more severe: “They told 4.32 million people [who watched the show] something that was demonstrably not true.”

Upon inquiry by Popular Mechanics, the History Channel responded with a statement: “HISTORY has a team of investigators exploring the latest developments about Amelia Earhart, and we will be transparent in our findings. Ultimately, historical accuracy is most important to us and our viewers.”

New photo suggests Amelia Earhart may have survived

Patty Wagstaff’s airplane hangs inverted just feet from Earhart’s at the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum. A three-time U.S. National Aviation Aerobatic Champion and the first woman to achieve this honor, Wagstaff attributes her career choice to Earhart’s influence. It was because of Earhart’s example that Wagstaff pursued aviation as her profession.

“Amelia Earhart let me know that the possibility was there… (she) kept me believing,” Wagstaff revealed to Popular Mechanics. While Earhart’s legend has continued to flourish over eight decades, Wagstaff emphasizes the importance of recognizing that Earhart was not a myth but an ordinary woman who accomplished extraordinary feats.

“Amelia Earhart let me know that the possibility was there… [she] kept me believing.”

Wagstaff, Gillespie, and Cochrane all agree that unraveling the mystery behind Earhart and Noonan’s disappearance may not hold great significance. Gillespie asserts that nothing they find will alter the aviation history Earhart carved. When asked if she believes Earhart will ever be found, Wagstaff simply replies, “In a way, I hope they don’t.”

Does all this searching amount to a futile expenditure of time and money? Cochrane concedes it likely does, though the discovery of Earhart’s DNA or a submerged Electra could potentially illuminate this 80-year-old enigma. One thing, however, remains no mystery: Earhart endures as a source of inspiration for millions, whether seasoned aviators or young girls aspiring to emulate her example.

“She always wanted to carve a career out of (aviation) and she did,” asserts Cochrane. “For a woman to achieve that, it was extraordinary. She took tremendous risks… and served as a role model and embodiment of courage.”

FAQs

Q1: Did Amelia Earhart start flying planes at a young age?

A1: Yes, Amelia Earhart’s fascination with aviation began when she was just 23 years old. In 1920, she took her first plane ride, and from that moment on, she was determined to learn how to fly.

Q2: What motivated Amelia Earhart to attempt her solo flight across the Atlantic?

A2: Amelia Earhart was inspired by Charles Lindbergh’s historic solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927. Lindbergh’s achievement motivated her to set her own records in the field of aviation, eventually leading to her solo transatlantic flight in 1932.

Q3: Were there any other female aviators who influenced Amelia Earhart?

A3: Yes, one of Earhart’s influences was Neta Snook, the first woman to run her own aviation business. Snook taught Earhart to fly and became her mentor, encouraging her to pursue a career in aviation.

Q4: Did Amelia Earhart face any challenges as a female pilot in a male-dominated industry?

A4: Absolutely, Amelia Earhart faced numerous challenges as a female pilot in the 1930s. She often had to prove herself in a male-dominated industry, breaking gender barriers and inspiring generations of women to follow their dreams in aviation.

Q5: Apart from her aviation achievements, did Amelia Earhart have other interests or hobbies?

A5: Yes, besides her passion for flying, Amelia Earhart was an advocate for women’s rights and social issues. She was also a prolific writer, authoring several books and articles about her experiences in aviation and advocating for gender equality.**